|

Relentless Adventure

and Ambition

Introduction

Alexander was born in 356 BC. His father, King Philip of Macedonia, had united

Greece and had intended to free the Asiatic Greeks from Persian control. He also

coveted the riches of the Persian Empire to pay for his professional army. At Philip's

death, Alexander first quelled rebellions in Greece and then crossed the

Dardenelles1 to start, at the age of twenty years, his 2800 mile journey into Asia.

During his Asian campaigns, Alexander founded or refounded many cities to

administer the conquered territories. The greatest of these was Alexandria in Egypt.

From these cities, in territories later ruled by Alexander's successors, Greek culture

spread and for the next three centuries was dominant throughout much of the Middle

East. This hellenisation process lasted until the spread of Roman power towards the

end of the first century BC. It all stemmed from the brief career of one man, who died

at the age of 33.

Who really was the man known as Alexander the Great? In only thirteen years,

between 336 and 323 BC, he earned enough fame to fuel legends down through the

ages. Thirteen years of unrelenting drive, of amazing deeds. Here was a young man

able to inspire large troops of men to follow him in a whirlwind of conquests that

looks like a race against time. Perhaps he knew that fate would not grant him years

enough to conquer the whole world, as he could well have attempted. In fact, it has

I. The Dardenelles: An isthmus in present North-West Turkey linking the Aegean Sea with the sea of Marmara.

Page-95

been said that the greatest blessing in Alexander's life was his early death, and his

greatest good fortune was that the practical common sense of his followers pre-vented him from crossing the Ganges. Had Napoleon been similarly forced to recognise his limits, his end might have been as great as his beginning.

In Alexande's case, it is remarkable that one of the greatest thinkers in world

history, Aristotle, was his teacher. It can safely be assumed that Aristotle gave his

pupil an enormous wealth of information and some degree of intimacy with the

teachings of Socrates and Plato. Alexander surely must have known that man could

attain his highest well-being only by acquiring a knowledge that would lead him to

do the right action voluntarily. This was the very teaching of Socrates: "Virtue is

knowledge." Alexander also must have learned the ethical doctrine of Aristotle

himself, according to whom virtue meant a mean between extremes. Aristotle was the

first logician of the Western world and he must have taught his pupil the art and

science of reasoning as applied to metaphysics, science and mathematics. The vast

encyclopedic knowledge that Aristotle could have put at Alexander's disposal would

have made Alexander, if he so chose, a great master of knowledge. Why, we may ask,

did this not happen? What exactly was the determining factor that made Alexander

a conqueror of lands and men instead of an expert scholar or an illumined sage?

Did Alexander ever ask himself, consciously and reflectively, what his aim of life

should be? We do not know with any certainty. Considering, however, that he had

access to wide fields of knowledge, such a question could hardly have escaped him.

But even if he asked this question, did he set about to find an answer?

Physically, he was an ideal youth, good in every sport. He possessed a wild

energy that would make him shoot arrows at any passing object, or alight from and

remount his chariot at full speed. During campaigns, if the going was slow, he would

go hunting alone and on foot and do combat with wild animals, however dangerous.

He liked hard work and hazardous deeds. He was usually sober and, apparently, in

very good health, since his body was credited with a pleasant fragrance. Beyond the

exaggerations of fame and legend, Alexander was certainly quite handsome, with

expressive features, soft blue eyes and luxuriant auburn hair.

Alexander is a striking example of what life-force can do in a man. More often

than not, human beings are led to their career or their life's work by temperament,

by likes and dislikes, and by their inner drives. The life-force in man seeks acquisition, possession, enjoyment, relationship, battle and conquest. It is often instinctive and therefore irresistible. Accordingly, it is not easy for a human being driven

by an extraordinary executive power and force of accomplishment to become

Page-96

intellectualised. This does not mean that the intellectualisation of life energy is

impossible, but it is evident that the tasks involved in such a process are enormous

and extremely difficult.

Alexander was primarily interested in adventure. He was verily a Prince of Air,

ready to fly on the wings of time just to discover novelties and unexpected

experiences. His ambitions were deep-seated and illimitable. In fact, it seems that

his aim of life was determined by the pressure of his ambitions rather than by any

rational system of thought or any ethical discipline. He was probably so prodigious

that he found it difficult to contain his energy. He brings to mind quicksilver: pursue

as you may, he is always one step ahead. He did not like the idea of rest and said

that sleep only served to remind him of his mortal condition. So many things to do,

so much to learn, so many possibilities.... He brings to mind too the echo of a

perpetual galloping on the quickest of horses.... The bursting life-force inside him

was quite evidently overwhelming, as was the call of the sirens of adventure and

ambition.

Mentally, he was very active and had a passion for study. His intellectual

abilities could never be used fully due to the early responsibilities that fell upon him

—hence, a lack of maturity of mind. As often is the case with great men of action,

he would always regret not having become a great thinker as well. Even after an

exhausting day of marching or fighting, he would delight in spending half the night

conversing -with scholars or scientists. King at twenty, absorbed in warfare and

administration, he had no chance to complete his education. He was brilliant, but

prone to errors in politics and warfare. He tended to be excessively superstitious,

despite his broadmindedness. Capable of leading armies, of conquering millions of

people, he was often unable to control his temper. Generally blind to his own faults

or limitations, he too frequently allowed his judgement to be obscured by praise.

Similar contradictions can be seen in his moral character. Naturally sentimental and

emotional, he could be moved to tears by poetry and music. He was exceptional in

friendship, very trusting and warm. He cared for his soldiers and avoided risking

their lives needlessly. Besieged cities would often open their gates to him, confident

in his reputation for generosity. Yet he could suddenly turn ferocious and resort to

excessive cruelty for which he would later feel great remorse.

Despite his youth and lack of experience, he was a good administrator, ruling

his empire with kindness and firmness. He respected agreements, and did not allow

his appointees to oppress his subjects. He had all the potential of a great statesman,

hut was not given enough time to mature in that dimension. He was driven by the

Page-97

vision of a united eastern Mediterranean world and, above all, of a fertile

cross-breeding of many cultures under the umbrella of Greek civilisation. This was

more an instinctive feeling than a product of reflection. Men like Alexander are often

seized by blazing intuitions, but these often get mixed with their more fundamental

ambitious drive.

A study of Alexander the Great is instructive in several ways. Firstly, it shorn

us what the life-force in man can achieve under circumstances and conditions as

favourable as Alexander's, and yet what failures attend unbridled adventure.

Secondly, it shows us that the human personality has far richer potentials than is

normally suspected. Thirdly, it gives us a chance to understand ourselves better, for

though we have a hundred and more limitations, we may discover, if we look closely

within ourselves, that there is in us the same life-force as we find in Alexander. In

other words, we discover that somewhere within our being we have basic instincts

and impulses, a universe of pressing desires, deep-seated attractions and

repulsions,

and longings and ambitions.

Had he lived longer, would Alexander have been able to control his wild

nature? A better control of his passions probably would have given him a deeper

sense of fulfilment in his achievements. Life-force may be exhilarating, but

to attain

superior human realisation it needs to be transformed and put in its proper place

along with the other energies that meet in man. No doubt this prodigious young king

was faced with a very difficult task in that respect. But the extraordinary profile of

him painted for us by Plutarch may be very instructive when we ourselves are

confronted with the quest of our aim of life.

Page-98

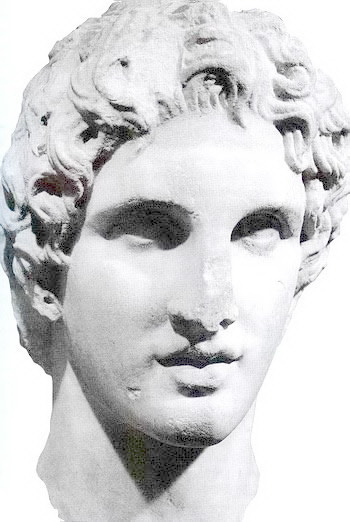

The best likeness of Alexander which has been preserved for us is to be found

in the statues sculpted by Lysippus, the only artist whom Alexander

considered worthy to represent him. Alexander possessed a number of

individual features which many of Lysippus' followers later tried to reproduce, for

example, the poise of the neck which was tilted slightly to the left, or a certain

melting look in his eyes, and the artist has exactly caught these peculiarities. On the

other hand when Apelles painted Alexander wielding a thunderbolt, he did not

reproduce his colouring at all accurately. He made Alexander's complexion appear

too dark-skinned and swarthy, whereas we are told that he was fair-skinned, with a

ruddy tinge that showed itself especially upon his face and chest. Aristoxenus also

tells us in his memoirs that Alexander's skin was fresh and sweet-smelling, and that

his breath and the whole of his body gave off a peculiar fragrance' which permeated

the clothes he wore....

Even while he was still a boy, he gave plenty of evidence of his powers of

self-control. In spite of his vehement and impulsive nature, he showed little interest

in the pleasures of the senses and indulged in them only with great moderation, but

his passionate desire for fame implanted in him a pride and a grandeur of vision

which went far beyond his years. And yet it was by no means every kind of glory

that he sought, and, unlike his father, he did not seek it in every form of action.

Philip, for example, was as proud of his powers of eloquence as any sophist, and

took care to have the victories won by his chariots at Olympia stamped upon his

coins. But Alexander's attitude is made clear by his reply to some of his friends,

when they asked him whether he would be willing to compete at Olympia, since he

was a fine runner. "Yes," he answered, "if I have kings to run against me." He seems

in fact to have disapproved of the whole race of trained athletes. At any rate although

he founded a great many contests of other kinds, including not only the tragic drama

and performances on the flute and the lyre, but also the reciting of poetry, fighting

with the quarter-staff and various forms of hunting, yet he never offered prizes either

for boxing or for the pancration.2

On one occasion some ambassadors from the king of Persia arrived in

Macedon, and since Philip was absent, Alexander received them in his place. He

talked freely with them and quite won them over, not only by the friendliness of his

manner, but also because he did not trouble them with any childish or trivial

inquiries, but questioned them about the distances they had traveled by road, the

nature of the journey into the interior of Persia, the character of the king, his

experience in war, and the military strength and prowess of the Persians. The

Page-99

ambassadors were filled with admiration. They came away convinced that Philip's

celebrated astuteness was as nothing compared to the adventurous spirit and lofty

ambitions of his son. At any rate, whenever he heard that Philip had captured some

famous city or won an overwhelming victory, Alexander would show no pleasure at

the news, but would declare to his friends, "Boys, my father will forestall me in

everything. There will be nothing great or spectacular for you and me to show the

world." He cared nothing for pleasure or wealth but only for deeds of valour and

glory, and this was why he believed that the more he received from his father, the

less would be left for him to conquer. And so every success that was gained by

Macedonia inspired in Alexander the dread that another opportunity for action had

been squandered on his father. He had no desire to inherit a kingdom which offered

him riches, luxuries and the pleasures of the senses: his choice was a life of struggle,

of wars, and of unrelenting ambition....

There came a day3 when Philoneicus the Thessalian brought Philip a horse

named Bucephalas,4 which he offered to sell for thirteen talents. The king and his

friends went down to the plain to watch the horse's trials, and came to the conclusion

that he was wild and quite unmanageable, for he would allow no one to mount him,

nor would he endure the shouts of Philip's grooms, but reared up against anyone

who approached him. The king became angry at being offered such a vicious animal

unbroken, and ordered it to be led away. But Alexander, who was standing close by,

remarked, "What a horse they are losing, and all because they don't know how to

handle him, or dare not try!" Philip kept quiet at first, but when he heard Alexander

repeat these words several times and saw that he was upset, he asked him, "Are you

finding fault with your elders because you think you know more than they do, or can

manage a horse better?" "At least I could manage this one better", retorted ,

Alexander. "And if you cannot," said his father, "what penalty will you pay for being

so impertinent?" "I will pay the price of the horse,"5 answered the boy. At this the

whole company burst out laughing, and then as soon as the father and son had settled

the terms of the bet, Alexander went quickly up to Bucephalas, took hold of his

bridle, and turned him towards the sun, for he had noticed that the horse was shying

at the sight of his own shadow, as it fell in front of him and constantly move

whenever he did. He ran alongside the animal for a little way, calming him down b

stroking him, and then, when he saw he was full of spirit and courage, he quietly

threw aside his cloak and with a light spring vaulted safely on to his back. For a little

while he kept feeling the bit with the reins, without jarring or tearing his

mouth, and

got him collected. Finally, when he saw that the horse was free of his fears and

Page-100

impatient to show his speed, he gave him his head and urged him forward, using a

commanding voice and a touch of the foot.

At first Philip and his friends held their breath and looked on in an agony of

suspense, until they saw Alexander reach the end of his gallop, turn in full control,

and ride back triumphant and exulting in his success. Thereupon the rest of the

company broke into loud applause, while his father, we are told, actually wept for

joy, and when Alexander had dismounted he kissed him and said, "My boy, you must

find a kingdom big enough for your ambitions. Macedonia is too small for you."

Philip had noticed that his son was self-willed, and that while it was very

difficult to influence him by force, he could easily be guided towards his duty by an

appeal to reason, and he therefore made a point of trying to persuade the boy rather

than giving him orders. Besides this he considered that the task of training and

educating his son was too important to be entrusted to the ordinary run of teachers

of poetry, music and general education: it required, as Sophocles puts it

The rudder's guidance and the curb's restraint,

and so he sent for Aristotle,6 the most famous and learned of the philosophers of his

time, and rewarded him with the generosity that his reputation deserved. Aristotle was

a native of the city of Stageira, which Philip had himself destroyed. He now repopulated it and brought back all the citizens who had been enslaved or driven into exile.

He gave Aristotle and his pupil the temple of the Nymphs near Mieza as a place

where they could study and converse, and to this day they show you the stone seats

and shady walks which Aristotle used. It seems clear too that Alexander was

instructed by his teacher not only in the principles of ethics and politics, but also in

those secret and more esoteric studies which philosophers do not impart to the

general run of students, but only by word of mouth to a select circle of the initiated.

Some years later, after Alexander had crossed into Asia, he learned that Aristotle had

published some treatises dealing with these esoteric matters, and he wrote to him in

blunt language and took him to task for the sake of the prestige of philosophy. This

was the text of his letter:

Alexander to Aristotle, greetings. You have not done well to write down and publish

those doctrines you taught me by word of mouth. What advantage shall I have over

other men if these theories in which 1 have been trained are to be made common

property? I would rather excel the rest of mankind in my knowledge of what is best

than in the extent of my power. Farewell...

Page-101

(Throughout his life, Alexander was to show an interest in "all kinds of learning" and

was "a lover of books" thanks to Aristotle's influence. The relationship between

Alexander and Philip, his father, took a turn for the worse, probably under the

influence of Alexander's mother, Olympias, whose relations with her husband soon

became bitter. Alexander was only twenty when Philip was assassinated by a member

of his court.)

His kingdom at that moment was beset by formidable jealousies and feuds and

external dangers on every side. The neighbouring barbarian tribes were eager to

throw off the Macedonian yoke and longed for the rule of their native kings: as for

the Greek States, although Philip had defeated them in battle, he had not had time to

subdue them or accustom them to his authority. He had swept away the existing

governments, and then, having prepared their peoples for drastic changes, had left

them in turmoil and confusion, because he had created a situation which was

completely unfamiliar to them. Alexander's Macedonian advisers feared that a crisis

was at hand and urged the young king to leave the Greek States to their own devices

and refrain from using any force against them. As for the barbarian tribes, they

considered that he should try to win them back to their allegiance by using milder

methods, and forestall the first signs of revolt by offering them concessions.

Alexander, however, chose precisely the opposite course, and decided that the only

way to make his kingdom safe was to act with audacity and a lofty spirit, for he was

certain that if he were seen to yield even a fraction of his authority, all his enemies

would attack him at once. He swiftly crushed the uprisings among the barbarians by

advancing with his army as far as the Danube, where he overcame Syrmus, the king

of the Triballi, in a great battle. Then when the news reached him that the Thebans

had revolted and were being supported by the Athenians, he immediately marched

south through the pass of Thermopylae. "Demosthenes," he said, "called me a boy

while I was in Illyria and among the Triballi, and a youth when I was marching

through Thessaly; I will show him I am a man by the time I reach the walls of

Athens...."

(Having taken Thebes, which resisted courageously, Alexander set a terrible example

by sacking the city. Probably feeling some remorse about this, he showed leniency

towards Athens.)

In the previous year a congress of the Greek states had been held at the Isthmus

of Corinth: here a vote had been passed that the states should join forces with

Page-102

Alexander in invading Persia and that he should be commander-in-chief of the

expedition. Many of the Greek statesmen and philosophers visited him to offer their

congratulations, and he hoped that Diogenes of Sinope, who was at that time living

in Corinth, would do the same. However since he paid no attention whatever to

Alexander, but continued to live at leisure in the suburb of Corinth which was known

as Craneion, Alexander went in person to see him and found him basking at full

length in the sun. When he saw so many people approaching him, Diogenes raised

himself a little on his elbow and fixed his gaze upon Alexander. The king greeted

him and inquired whether he could do anything for him. "Yes," replied the

philosopher, "you can stand a little to one side out of my sun." Alexander is said to

have been greatly impressed by this answer and full of admiration for the hauteur

and independence of mind of a man who could look down on him with such

condescension. So much so that he remarked to his followers, who were laughing

and mocking the philosopher as they went away, "You may say what you like, but if

I were not Alexander, I would be Diogenes."

Next he visited Delphi, because he wished to consult the oracle of Apollo7

about the expedition against the Persians. It so happened that he arrived on one of

those days which are called inauspicious, when it is forbidden for the oracle to

deliver a reply. In spite of this he sent for the prophetess, and when she refused to

officiate and explained that the law forbade her to do so, he went up himself and

tried to drag her by force to the shrine. At last, as if overcome by his persistence,

she exclaimed, "You are invincible, my son!" and when Alexander heard this, he

declared that he wanted no other prophecy, but had obtained from her the oracle he

was seeking. When the time came for him to set out, many other prodigies attended

the departure of the army: among these was the phenomenon of the statue of

Orpheus which was made of cypress wood and was observed to be covered with

sweat. Everyone who saw it was alarmed at this omen, but Aristander urged the king

to take courage, for this portent signified that Alexander was destined to perform

deeds which would live in song and story and would cause poets and musicians

much toil and sweat to celebrate them.

As for the size of his army, the lowest estimate puts its strength at 30,000

infantry and 4,000 cavalry and the highest 43,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry.8

According to Aristobulus the money available for the army's supplies amounted to

no more than seventy talents. Douris says that there were supplies for only thirty

days, and Onesicritus that Alexander was already two hundred talents in debt. Yet

although he set out with such slender resources, he would not go aboard his ship

Page-103

Darius, king of Persia

until he had discovered the circumstances of all his companions and had assigned an

estate to one, a village to another, or the revenues of some port or community to a

third. When he had shared out or signed away almost all the property of the crown,

Perdiccas asked him, "But your majesty, what are you leaving for yourself?" "My

hopes!" replied Alexander. "Very well, then," answered Perdiccas, "those who serve

with you will share those too." With this, he declined to accept the prize which had

been allotted to him, and several of Alexander's other friends did the same. However

those who accepted or requested rewards were lavishly provided for, so that in the

end Alexander distributed among them most of what he possessed in Macedonia.

These were his preparations and this was the adventurous spirit in which he crossed

the Hellespont.

Once arrived in Asia, he went up to Troy, sacrificed to Athena and poured

Page-104

libations to the heroes of the Greek army. He anointed with oil the column which

marks the grave of Achilles, ran a race by it naked with his companions, as the

custom is, and then crowned it with a wreath: he also remarked that Achilles was

happy in having found a faithful friend while he lived and a great poet to sing of his

deeds after his death. While he was walking about the city and looking at its ancient

remains, somebody asked him whether he wished to see the lyre which had once

belonged to Paris." "I think nothing of that lyre," he said, "but I wish I could see

Achilles' lyre, which he played when he sang of the glorious deeds of brave men."

Meanwhile Darius' generals had gathered a large army and posted it at the

crossing of the river Granicus, so that Alexander was obliged to fight at the very

gates of Asia, if he was to enter and conquer it. Most of the Macedonian officers

were alarmed at the depth of the river and of the rough and uneven slopes of the

banks on the opposite side, up which they would have to scramble in the face of the

enemy. There were others too who thought that Alexander ought to observe the

Macedonian tradition concerning the time of year, according to which the kings of

Macedonia never made war during the month of Daesius.10 Alexander swept aside

these scruples by giving orders that the month should be called a second Artemisius.

And when Parmenio advised him against risking the crossing at such a late hour of

the day, Alexander declared that the Hellespont would blush for shame if, once he

had crossed it, he should shrink back from the Granicus; then he immediately

plunged into the stream with thirteen squadrons of cavalry.11It seemed the act of a

desperate madman rather than a prudent commander to charge into a swiftly flowing

river, which swept men off their feet and surged about them, and then to advance

through a hail of missiles towards a steep bank which was strongly defended by

infantry and cavalry. But in spite of this he pressed forward and with a tremendous

effort gained the opposite bank, which was a wet treacherous slope covered with

mud. There he was immediately forced to engage the enemy in a confused hand to

hand struggle, before the troops who were crossing behind him could be organised

into any formation. The moment his men set foot on land, the enemy attacked them

with loud shouts, matching horse against horse, thrusting with their lances and

fighting with the sword when their lances broke. Many of them charged against

Alexander himself, for he was easily recognisable by his shield and by the tall white

plume which was fixed upon either side of his helmet.

(The battle went on.... Alexander was saved by Cleitus. Finally, the Persians were

routed......)

Page-105

The Persians are said to have lost twenty thousand infantry and two thousand

five hundred cavalry, whereas on Alexander's side, according to Aristobulus, only

thirty-four soldiers in all were killed, nine of them belonging to the infantry.

Alexander gave orders that each of these men should have his statue set up in bronze

and the work was carried out by Lysippus. At the same time he was anxious to give

the other Greek states a share in the victory. He therefore sent the Athenians in

particular three hundred of the shields captured from the enemy, and over the rest of

the spoils he had this proud inscription engraved:

Alexander, the son of Philip, and all the Greeks, with the exception of the Spartans,

won these spoils of war from the barbarians who dwell in Asia....

(The result of this victory was "a great and immediate change in Alexander's

situation ". Many cities made their submission. Alexander marched on and cleared the

coast of Asia Minor as far as Cilicia and Phoenicia.)

Next he marched into Pisidia where he subdued any resistance which he

encountered, and then made himself master of Phrygia. When he captured Gordium,

which is reputed to have been the home of the ancient king Midas, he saw the

celebrated chariot which was fastened to its yoke by the bark of the cornel-tree, and

heard the legend which was believed by all the barbarians, that the fates had decreed

that the man who untied the knot was destined to become the ruler of the whole

world. According to most writers the fastenings were so elaborately intertwined and

coiled upon one another that their ends were hidden: in consequence Alexander did

not know what to do, and in the end loosened the knot by cutting through it with his

sword, whereupon the many ends sprang into view....

(Then Alexander wanted to invade the interior. But Darius was marching upon the

coast from Susa.)

Darius was encouraged by the many months of apparent inactivity which

Alexander had spent in Cilicia, for he imagined that this was due to cowardice. In fact

the delay had been caused by sickness, which some said had been brought on by

exhaustion, and others by bathing in the icy waters of the river Cydnus. At any rate

none of his other physicians dared to treat him, for they all believed that his condition

was so dangerous that medicine was powerless to help him, and dreaded the

accusations that would be brought against them by the Macedonians in the event of

Page-106

Alexander young

Page - 107

their failure. The only exception was Philip, an Acarnanian, who saw that the King

was desperately ill, but trusted to their mutual friendship. He thought it shameful

not

to share his friend's danger by exhausting all the resources of his art even at the risk

of his own life, and so he prepared a medicine and persuaded him to drink it with out

fear, since he was so eager to regain his strength for the campaign. Meanwhile

Parmenio had sent Alexander a letter from the camp warning him to beware of Philip

since Darius, he said, had promised him large sums of money and even the hand of

his daughter if he would kill Alexander. Alexander read the letter and put it

under his

pillow without showing it to any of his friends. Then at the appointed hour, when

Philip entered the room with the king's companions carrying the medicine in a cup

Alexander handed him the letter and took the draught from him cheerfully and

without the least sign of misgiving. It was an astonishing scene, and one well worthy

of the stage — the one man reading the letter and the other drinking the physic,

and

then each gazing into the face of the other, although not with the same expression. The

king's serene and open smile clearly displayed his friendly feelings towards Philip

and his trust in him, while Philip was filled with surprise and alarm at the accusation

at one moment lifting his hands to heaven and protesting his innocence before the

gods, and the next falling upon his knees by the bed and imploring Alexander to take

courage and follow his advice. At first the drug completely overpowered him and, as

it were, drove all his vital forces out of sight: he became speechless, fell into a swoon,

and displayed scarcely any sign of sense or of life. However, Philip quickly restored

him to consciousness, and when he had regained his strength he showed himself to

the Macedonians, who would not be consoled until they had seen their king....

(Alexander won the big battle that followed. Darius was forced to take flight, leaving

behind his mother, wife, daughters and a luxurious tent with many treasures. Alexander

behaved in a chivalrous way towards the women, respecting and protecting them

contrary to the customs of his time.)

Alexander was also more moderate in his drinking than was generally

supposed. The impression that he was a heavy drinker arose because when he had

nothing else to do, he liked to linger over each cup, but in fact he was usually talking

rather than drinking; he enjoyed holding long conversations, but only when he had

plenty of leisure. Whenever there was urgent business to attend to, neither wine, nor

sleep, nor sport, nor sex, nor spectacle, could ever distract his attention, as they did

for other generals. The proof of this is his life-span which although so short, was

Page-108

filled to overflowing with the most prodigious achievements. When he was at

leisure, his first act after rising was to sacrifice to the gods, after which he took his

breakfast sitting down.12 The rest of the day would be spent in hunting, administering

justice, planning military affairs or reading. If he were on a march which required

no great haste, he would practise archery as he rode, or mounting and dismounting

from a moving chariot, and he often hunted foxes or birds, as he mentions in his

journals. When he had chosen his quarters for the night and while he was being

refreshed with a bath or rubbed down, he would ask his cooks and bakers whether

the arrangements for supper had been suitably made.

His custom was not to begin supper until late, as it was growing dark. He took

it reclining on a couch, and he was wonderfully attentive and observant in ensuring

that his table was well provided, his guests equally served, and none of them

neglected. He sat long over his wine, as I have remarked, because of his fondness

for conversation. And although at other times his society was delightful and his

manner full of charm beyond that of any prince of his age, yet when he was drinking

he would sometimes become offensively arrogant and descend to the level of a

common soldier, and on these occasions he would allow himself not only to give

way to boasting but also to be led on by his flatterers. These men were a great trial

to the finer spirits among his companions, who had no desire to compete with them

in their sycophancy, but were unwilling to be out-done in praising Alexander. The

one course they thought shameful, but the other was dangerous. When the drinking

was over it was his custom to take a bath and sleep, often until midday, and

sometimes for the whole of the following day....

(For many years, Alexander continued his campaigns and further and further enlarged

his empire. To make submission easier for his subjects, he proclaimed himself a God.

He adopted more and more fully the customs and ways of living of the "barbarians",

much to the displeasure of many Macedonians. Finally, he set his eyes upon India.)

Alexander was now about to launch his invasion of India. He had already taken

note that his army was over-encumbered with booty and had lost its mobility, and so

early one morning after the baggage waggons had been loaded, he began by burning

those which belonged to himself and the Companions13

and then gave orders to set

fire to those of the Macedonians. In the event his decision proved to have been more

difficult to envisage than it was to execute. Only a few of the soldiers resented it: the

great majority cheered with delight and raised their battle-cry: they gladly shared out

the necessities for the campaign with those who needed them and then they helped

Page-109

to burn and destroy any superfluous possessions with their own hands. Alexander

was filled with enthusiasm at their spirit and his hopes rose to their highest pitch. By

this time he was already feared by his men for this relentless severity in punishing

any dereliction of duty. For example he put to death Menander, one of the

Companions, because he had been placed in command of a garrison and had refused

to remain there, and he shot down with his own hand one of the barbarians named

Orsodates who had rebelled against him.14

(Certain portents, at first unsettling, were finally considered encouraging. But the

campaign was likely to be arduous....)

This was certainly how events turned out. Alexander

encountered many dangers in the battles he fought and was severely

wounded, but the greatest losses his army

suffered were caused by lack of provisions and by the rigours of the

climate. But for his part he was anxious to prove that boldness can triumph over

fortune and courage over superior force; he was convinced that while there are no

defences so impregnable that they will keep out the brave man, there are likewise

none so strong that they will keep the coward safe. It is said that when he was

besieging the fortress of a ruler named Sisimithres, which was situated upon a steep

and inaccessible rock, his soldiers despaired of capturing it. Alexander asked

Oxyartes whether Sisimithres himself was a man of spirit and received the reply that

he was the greatest coward in the world. "Then what you are telling me", Alexander

went on, "is that we can take the fortress, since there is no strength in its defender."

(And, in fact, he did capture it by playing upon the other's fear.)

The events of the campaign against Porus are described in Alexander's letters,

He tells us that the river Hydaspes flowed between the two camps, and that Porus

stationed his elephants on the opposite bank and kept the crossing continually

watched. Alexander caused a great deal of noise and commotion to be made day

after day in his camp and in this way accustomed the barbarians not to be alarmed

by his movements.15 Then at last on a stormy and moonless night he took a part of

his infantry and the best of his cavalry, marched some distance along the river past

the enemy's position, and then crossed over to a small island. Here he was overtaken

by a violent storm of rain accompanied by tremendous bursts of thunder and

lightning. Although he saw that a number of his men were struck dead by the

lightning, he continued the advance and made for the opposite bank. After the storm

Page-110

the Hydaspes, which was roaring down in high flood, had scooped out a deep

channel, so that much of the stream was diverted in this direction and the ground

between the two currents had become broken and slippery and made it impossible

for his men to gain a firm footing. It was on this occasion that Alexander is said to

have exclaimed, "0 you Athenians, will you ever believe what risks I am running

just to earn your praise?"...

(Then a very difficult battle followed which was finally won after a stubborn hand-to-

hand struggle.)

Most historians agree that Porus was about six feet three inches tall, and that

his size and huge physique made him appear as suitably mounted upon an elephant

as an ordinary man looks on a horse. His elephant too was very large and showed an

extraordinary intelligence and concern for the king's person. So long as Porus was

fighting strongly it would valiantly defend him and beat off his attackers, but as soon

as it recognised that its master was growing weak from the thrusts and missiles that

had wounded him, it knelt quietly on the ground for fear that he might fall off, and

with its trunk took hold of each spear and drew it out of his body. When Porus was

taken prisoner, Alexander asked him how he wished to be treated. "As a king", Porus

answered, and when Alexander went on to ask whether he had anything more to say,

the reply came, "Those words, 'as a king' include everything." At any rate Alexander

not only allowed him to govern his former kingdom, but he also added to it a

province, which included the territory of the independent peoples he had subdued.

These are said to have numbered fifteen nations, five thousand towns of

considerable size, and innumerable villages. His other conquests embraced an area

three times the size of this, and he appointed Philip, one of the Companions, to rule

it as satrap....

Another consequence of this battle with Porus was that it blunted the edge of

the Macedonians' courage and made them determined not to advance any further into

India. It was only with great difficulty that they had defeated an enemy who had put

into the field no more than twenty thousand infantry and two thousand cavalry, and

so, when Alexander insisted on crossing the Ganges,16 they opposed him outright.

The river, they were told, was four miles across and one hundred fathoms deep, and

the opposite bank swarmed with a gigantic host of infantry, horsemen and elephants.

It was said that the kings of the Gandaridae and the Praesii were waiting for

Alexander's attack with an army of eighty thousand cavalry, two hundred thousand

Page-111

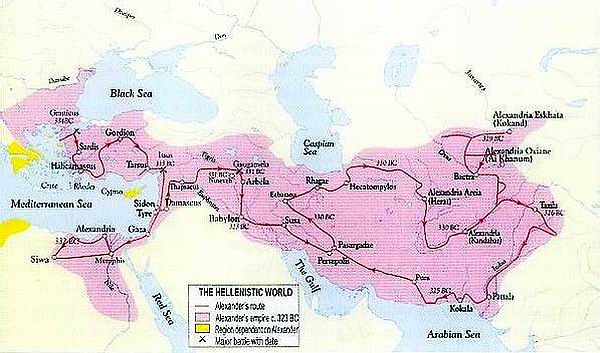

Alexander's empire

infantry, eight thousand chariots and six thousand fighting elephants, and this report

was no exaggeration, for Sandrocottus, the king of this territory who reigned there

not long afterwards, presented five hundred elephants to Seleucus, and overran and

conquered the whole of India with an army of six hundred thousand men.

At first Alexander was so overcome with disappointment and anger that he shut

himself up and lay prostrate in his tent. He felt that unless he could cross the Ganges,

he owed no thanks to his troops for what they had already achieved; instead he

regarded their having turned back as an admission of defeat. However his friends set

themselves to reason with him and console him and the soldiers crowded round the

entrance to his tent, and pleaded with him, uttering loud cries and lamentations, until

finally he relented and gave orders to break camp. But when he did so he devised a

number of ruses and deceptions to impress the inhabitants of the region. For example

he had arms, horses' mangers and bits prepared, all of which exceeded the normal

size or height or weight, and these were left scattered about the country. He also set

up altars for the gods of Greece and even down to the present day the kings of the

Praesii whenever they cross the river do honour to these and offer sacrifice on them

Page-112

in the Greek fashion. Sandrocottus, who was then no more than a boy, saw

Alexander himself, and we are told that in later years he often remarked that

Alexander was within a step of conquering the whole country, since the king who

ruled it at that time was hated and despised because of his vicious character and his

lowly birth...

(Wanting to see the outer Ocean, Alexander built rafts to travel on the river, landing

here and there to take cities... When he finally returned from India, he brought back

only a quarter of his fighting force. He was confronted with the abuses of many of those

that he had put in charge of parts of his empire. Alexander became more and more like

a "barbarian " and showed an increasing concern with the occult...)

Meanwhile Alexander had become so much obsessed by his fears of the

supernatural and so overwrought and apprehensive in his own mind, that he inter-

preted every strange or unusual occurrence, no matter how trivial, as a prodigy or a

portent, with the result that the place was filled with soothsayers, sacrificers,

purifiers and prognosticators. Certainly it is dangerous to disbelieve or show

contempt for the power of the gods, but it is equally dangerous to harbour super-

stition, and in this case just as water constantly gravitates to a lower level, so

unreasoning dread filled Alexander's mind with foolish misgivings, once he had

become a slave to his fears. However, when the verdict of the oracle concerning

Hephaestion was brought to him,17 he laid aside his grief and allowed himself to

indulge in a number of sacrifices and drinking-bouts. He gave a splendid banquet in honour of Nearchus, after which he took a bath as his custom was, with the intention

of going to bed soon afterwards. But when Medius invited him, he went to his house

to join a party, and there after drinking all through the next day, he began to feel

feverish. This did not happen "as he was drinking from the cup of Hercules",18 nor

did he become conscious of a sudden pain in the back as if he had been pierced by

a spear: these are details with which certain historians felt obliged to embellish the

occasion, and thus invent a tragic and moving finale to a great action. Aristobulus

tells us that he was seized with a raging fever, that when he became very thirsty he

drank wine which made him delirious, and that he died on the thirtieth day of the

month Daesius.

Text from Plutarch, Parallel Lives, translation by lan Scott-Kilvert

in The Age of Alexander (Penguin Books, 1983), p. 255 ff.

Page-113

Notes

-

This fragrance was also regarded as a sign of his superhuman nature.

-

A contest which combined wrestling and boxing.

-

The date is uncertain. Alexander may have been about fourteen. Thessaly was the fine

breeding-ground for horses in Greece.

-

The name of a famous breed of Thessalian horses which were branded on the shoulder with tl

sign of an ox's head.

-

The speed of change of money-values makes it futile to try to convert the asking price i

thirteen talents into modem figures. It is enough to say that by the Greek standards of the tin

this was a very high price.

-

When Alexander was thirteen.

-

About the Oracle of Delphi, see foot-note n°l, p.62.

-

Modem estimates give totals of about 43,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry: about one quarter (

these were the advance guard, which had already crossed to Asia. The cavalry included as man Thessalians as Macedonians, while the other Greek city-states contributed about 7,000 infantry

and 600 cavalry. Besides the operational troops the expedition included reconnaissance staff and many other specialists — geographers, historians, astronomers, zoologists, etc.

-

There is a pun here: Paris was also known as Alexander.

-

May-June: this was the time for the gathering of the harvest.

-

Diodorus gives an account which is more plausible in military terms. According to this Alexander

marched downstream under cover of darkness, found a suitable ford, crossed at dawn, and ha

most of his infantry over before the Persians discovered the new position.

-

That is, not reclining, as for the evening meal.

-

The Companions were the members of Alexander's own cavalry regiment.

-

Alexander had reorganised the army to include some oriental troops especially among the

cavalry. His force for the invasion of India may have numbered some 35,000 fighting men.

-

Alexander could not get his horses to cross in the face of the elephants: the object of his repeated

feints was that Porus should cease to send out the elephants to meet every threat.

-

The date was September 326 BC. Alexander did not, of course, reach the Ganges. The river

where the troops mutinied was the Hyphasis: the upper Ganges was some two hundred and

fifty miles further east. There is much dispute as to his real intentions and whether he planned

to advance as far as the "eastern ocean",

-

Hephaestion: Macedonian General who was Alexander's closest friend. After his death in 324

BC, Alexander sent to inquire of the oracle of Ammon whether it was permitted to worship

Hephaestion as a god. According to certain sources, the answer was that Ammon permitted

sacrifice to be offered him as to a "hero" or demi-god, which pleased Alexander.

-

A "cup of Hercules" was a very large beaker, drained without heel-taps. It would imply in that

case that the wine drunk by Alexander was poisoned.

Page114

Plutarch

Plutarch was one of the last classical Greek historians. He was born around AD 46 at Chaeronea

in Boetia, and died sometime after AD 120. He was a student in the School of Athens, became a

philosopher, and wrote a large number of essays and dialogues on philosophical, scientific and

literary subjects (the Moralia). We know that he traveled widely in Egypt and went to Rome.

Plutarch wrote his historical works relatively late in life, and his Parallel Lives of eminent Greeks

and Romans is probably his best known and most influential work. As he states, his intention in the

Lives was to write biography, not history as such, and this is reflected in the choice of his sources.

He drew upon a very wide range of authorities, of quite unequal value. He felt his task was more

to create an inspiring portrait than to evaluate facts. At any rate, in the case of Alexander the Great,

his achievements, his influence on the world, and his personal character were certainly aweinspiring. That much was clearly perceived by Plutarch, and he did manage to communicate it in

the chapter on Alexander.

|

Ancient Greece and Alexander: A brief

outline

A civilisation appears to have emerged on mainland

Greece about 1600 BC. This came to be known as the

Mycenaean civilisation. Feudal warrior leaders ruled

their districts from hilltop fortresses, the principal fort

being Mycenae itself. Minoan Crete exercised a strong

influence in these early times; but, as Mycenaean Greece

gradually acquired knowledge of the sea, power shifted in

its favor. Feared as warriors, large mercenary

detachments fought for Crete and Egypt, among other

states,

The height of Mycenaean expansion and power was

reached between 1500 and 1300 BC. Eventually Crete,

the Cyclades, Rhodes, and Cyprus were annexed, and

vigorous trade was established throughout the

Mediterranean, even with the tribes of north and west

Europe. Weakened by internal strife and wars in Asia

Minor, Mycenae was overrun by invaders from central

Asia toward the end of the 12th century BC.

After the Mycenaean period, Greece was invaded by

Indo-European tribes from the north. The distribution of

peoples in Greece before the city states made for little

|

|

Page-115

unity, but they all took part in the Olympic Games. Greek colonies were established along much of

the perimeter of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, and Athens became the leading state after

the Persian advance was halted in the 5th century BC.

Fifth-century Greece was dominated by the Athenians. The Acropolis was the ancient hilltop

citadel of Athens, and its ruin still dominates the city today. Its buildings were constructed in the

second half of the 5th century BC. The greatest was the Parthenon, the temple dedicated to the

goddess Athena. Sparta, one of the city-states, had military ambitions and a well-trained

professional army. Athens and Sparta fought together against Persian attacks, but afterwards

became rivals. In the long Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) between Athens and Sparta, Athens

was defeated by Sparta, and Athens lost its empire.

The city-states of Greece continued to fight between themselves and particularly against Sparta

whose rule was very harsh. All the city states were much weakened by these constant battles and,

despite a last effort to unite against the invader from Macedonia, Philip, they lost and thus Greece

became at last unified under Macedonian rule, just before the birth of Alexander the Great in 356 BC.

State of the Civilised world in Alexander's time (around 330 BC)

For the Greeks of that time, civilisation was concentrated in the Mediterranean world. Besides

Greece and its city states, there was the immense Persian Empire which embraced nearly all of the

Middle East: Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine, the Phoenician cities and finally Egypt

were successively conquered by the Persians.

In the days of Alexander and Darius, no one would have thought that two centuries later Rome

would be able to unify the Ancient World. It was then a small city without a good harbour and not

much given to commerce. Nevertheless, two centuries after Alexander the Romans, having

dominated all of Italy, had already conquered Greece and were on their way to take over and unify

the Mediterranean world.

In India in 350 Be Buddhism was flourishing. At the time of Alexander's death, the Mauryan

dynasty was established (322 BC) and the first King of that dynasty, Chandragupta Maurya (322-

298 BC), came closer to uniting India than had any earlier ruler. Only the extreme South escaped

his domination.

What happened after Alexander

Alexander's sudden death meant that he had no time to consolidate his empire or to arrange for

an orderly succession. His Macedonian generals fought among themselves. Political disunity,

however, did not interfere with Alexander's vision of a commonwealth of peoples united by Greek

culture. All the successor states were dominated by Greeks and by natives who imitated the Greek

Page-116

way of life. And although the peasants and much of the urban population of the Middle East held

fast to their native cultures and native languages, scholars, administrators, and businessmen all

used Greek and were guided, to some degree, by Greek ideas and customs. This era in which the

Middle East was permeated by Greek influence is known as the Hellenistic period (The Greeks

called themselves Hellenes; Hellenistic means "Greek-like"). It ended politically in 30 BC, when

Rome annexed Egypt, the last nominally independent Hellenistic state. But the cultural unity of the

Middle East lasted far longer; it was broken only when the Moslems conquered Syria and Egypt in

the seventh century AD.

A few dates

|

356 BC |

Birth of Alexander. |

|

336 BC |

Alexander (aged 20) becomes king of Macedon

following the assassination of his father Philip.

|

|

334 BC |

Alexander crosses the Hellespont into Asia. |

|

332 BC |

Invasion of Egypt. Foundation of Alexandria |

|

331-328 BC |

Campaigns in Asia. |

|

327 BC |

Invasion of India.

|

|

324 BC |

return to Persia

|

|

323 BC |

Death of Alexander.

|

Suggestions for further reading

Badian, E. Alexander the Great and the Unity of Mankind. Historia, 1958, 425.44.

Bum, A. R. Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic World. 2nd ed. Macmillan, 1962.

Durant, Will. The Story of Civilization: Part II, The Life of Greece. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1966.

Green, Peter. Alexander the Great. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1970.

Alexander of Macedon. Penguin Books.

Hamilton, J. R. Alexander the Great. Hutchinson University Library, 1973.

Renault, Mary. The Nature of Alexander. England, Penguin Books, 1983.

Robinson, CA. The Extraordinary Ideas of Alexander the Great. American Hist. Review, 1957, 326-44.

Tam, Sir William, and Griffith, G. T. Hellenistic Civilization. Arnold, 3rd ed. 1952.

Page-117 |